Blog: Teaching in Ghana: Confronting Privilege and Power in Global Academia

By Dr. Jan Freihardt: Who gets to shape the global conversation on climate change—and why are so many voices from the Global South missing? During a teaching experience in Ghana, I was confronted with uncomfortable questions about historical inequalities, resource extraction, and the role of privileged academics in North-South collaborations. How can we foster more ethical and truly reciprocal knowledge exchanges?

It was Monday afternoon when I felt it for the first time. It started as a slight discomfort in my stomach and slowly crept up to my chest. By the evening, it had turned into an oppressive feeling, like I was wearing a tight corset.

Rewind. Two days earlier, I had arrived in Accra, Ghana, to teach a block course on “International Environmental Politics” at a local university. The 25 students came from different countries, mostly from Ghana, Nigeria, and Cameroon.

When we started the class on Monday morning, I asked the students to reflect on topics and questions they would like to explore during the block course. One of them wrote down: "How is it that the Global North, having caused most of climate change, is now using international agreements to dictate our environmental policies?" A valid point.

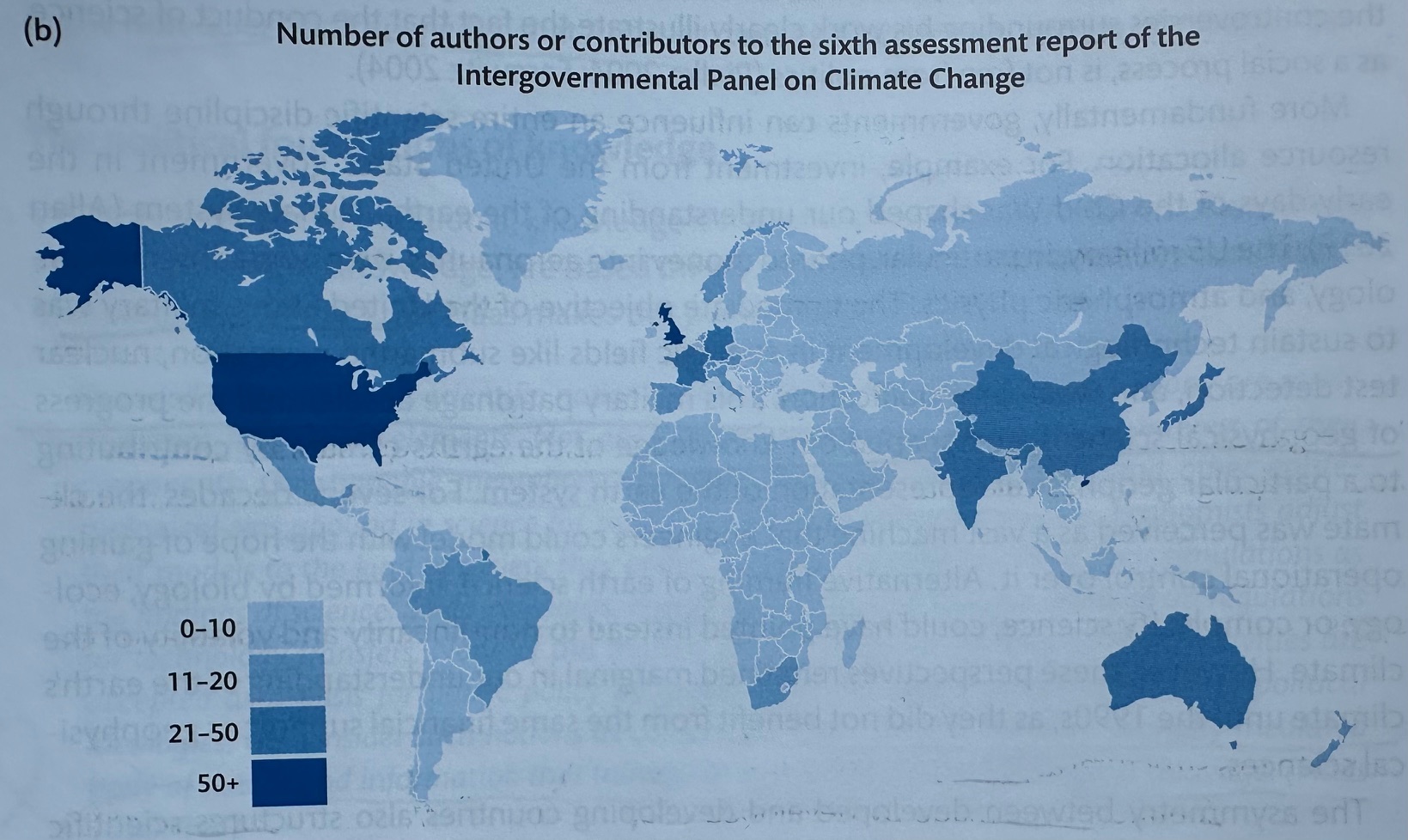

Next, we discussed the global science-policy interface, using the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as an example. As I pull up a map of the world showing the geographic distribution of IPCC authors, I hear the class murmur. Indeed, the picture is striking. The vast majority of authors are based in the Global North or the BRICS countries. Very few authors are based in Africa, Southeast Asia, Central America, or the Middle East, even though these regions are among the most vulnerable to climate change.

Why are all these countries not adequately represented? Are their scientific institutions simply not producing "good enough" science? Is it a coincidence? Probably not, in a world where knowledge is power. Rather, the imbalance reflects a global inequality that has its roots several centuries ago and is perpetuated by the current global geopolitical order.

West Africa, and Ghana in particular, played a central role in the triangular trade that began in the 16th century: European manufactured goods were shipped to Africa in exchange for slaves who were brought to the Americas to work on plantations. The resulting raw materials, such as sugar and cotton, were shipped back to Europe, feeding the manufacturing industry and completing the triangle. According to current estimates, external page approximately 12 million slaves were exported from Africa during the entire period of the Atlantic slave trade. In addition to the human tragedy, the effects of this slave trade are still felt today: Countries from which slaves were exported external page perform worse economically than countries from which no slaves were taken.

In addition to slaves, the colonial powers extracted vast amounts of natural resources from their African colonies. Under British colonial rule, Ghana, for example, was known as the "Gold Coast" because of its vast gold reserves. While traditional forms of mining were locally operated, the advent of modern extraction methods made gold mining an exclusively foreign-run enterprise, external page with profits flowing to European mining companies and the colonial government.

Unfortunately, not much has changed. Today, Ghana is the sixth largest gold producer in the world. But most of this material wealth flows abroad. For example, two of Ghana's largest mining companies - AngloGold Ashanti and Newmont - are British and American-owned, respectively.

Taken together, then, the lack of IPCC authors from African institutions (and, more generally, the lack of academic institutions that qualify as "good" by Global North standards) is far from accidental. It's the result of centuries of resource extraction - slaves and raw materials - combined with a modern geopolitical and economic world order that continues to send much larger flows of capital from South to North than the comparatively tiny amounts of "development aid" that flow from North to South:

“Poor countries are poor because they are integrated into the global economic system on unequal terms. The aid narrative hides the deep patterns of wealth extraction that cause poverty and inequality in the first place: rigged trade deals, tax evasion, land grabs and the costs associated with climate change.” Jason Hickel, external page The Divide

Which brings me back to the beginning and my growing discomfort during the first day of class. What am I - a white person from a highly privileged background - doing here? Isn't it cynical to teach students in Ghana how to properly manage their environment, coming from external page a country that heavily overuses natural resources and external page generates much of its wealth by exploiting the Global South?

In general, it seems a worthwhile approach to build capacity for research and teaching in-country, as is the goal of joint Master's programs between institutions from the Global South and from the Global North. However, I feel that this general intention needs to be accompanied by a mindset of humility and awareness of power dynamics and privileges on the part of the Global North partner. Only then can such an exchange at least approach the much quoted "eye level" and lead to mutual learning and understanding, as opposed to a one-way, top-down endeavor.

I am curious: Have you experienced similar dynamics in North-South teaching or research settings? What approaches have helped you to ethically navigate such spaces?

Share your experiences on our external page LinkedIn post or via email ().

Jan Freihardt has a background in environmental engineering and political science and is a former postdoctoral researcher in the Global Health Engineering group. His research focuses on climate-induced migration, climate adaptation, and air pollution.